Pong is about the beauty of synchronization, a tribal dance so rudimentary and primal that it’s impossible to ignore its rhythm. It’s a war of movement, an intense mano-a-mano trial of reflexes so often determined by a fraction of an inch. It spoke to the dawning of a new era, those rectangular paddles an obvious homage to the mystery and grandeur of 2001‘s (released just four years prior) evolution-baiting monolith.

Nah, I’m just messing with you. Pong is Pong, and if you’ve stuck with me so far, you probably have a pretty solid grasp on what it is and why it’s important. There’s no need to get too loquacious about the thing; I doubt many film surveys spend much time analyzing the finer points of Fred Ott’s Sneeze, either. Pong turned forty this month, and while retrospects abound, they wisely focus more on cultural impact than taking Paddle 1 and Paddle 2 for another lengthy spin. Outside of that celebration, the most you’ll usually hear about the game these days is when some half-informed news reporter does a story about whatever new blood-clogged war simulator just grossed $600 million in a single day, and concludes, with a smirk, “Whatever you think about that, video games sure have come a long way since Pong!“

Why write about Pong? It’s not a title anyone would find conspicuously absent from this blog, not a Half-Life or a Legend of Zelda (someday soon, I promise!) necessary for this sort of retrospective. It’s a conundrum I’ve debated since this project’s inception: do I write about Pac-Man? What about Donkey Kong or Asteroids? How could I even procure an interesting take on games so universal, so perfectly simplistic and introductory, so as to make their inclusion feel like something more than a tossed-off history lesson? As MoMA can attest, many of these games are delightful pieces of design and cultural iconography. But I don’t want to be the guy writing four-thousand word essays about how Dig Dug represents the game community’s view of itself as a subterranean culture or something. I’m already way too close to being that guy most days, and I don’t want to stretch my little schtick to its breaking point.

But I can’t in good conscience cover Spacewar! and not throw a bone to Pong as well. It’s the Beowulf to Spacewar!‘s Epic of Gilgamesh, so much more well-known and pored over that it barely feels like the work of human beings anymore, instead appearing as some natural monument as old and accepted as the hills. But I’d take the comparison further; like most high schoolers and college students, I was pretty sick of Beowulf by the second or third go-round. I just couldn’t find anything to grab onto in it, beyond it serving as a rough and frankly boring building block for the storytelling tradition. Yet reading the Epic of Gilgamesh in college was a revelation. Its themes were more resonant, its protagonist’s fear of death more palpable. I couldn’t get over how an even older story managed to convey fairly elaborate thoughts and views on what it meant (and still means) to be alive. While Spacewar! by its nature does not explore these sort of depths, researching it was a similar revelation to reading Gilgamesh: How the hell did they already get it so right? They are both arguably actual great works of their respective mediums, whereas Pong and Beowulf are almost solely interesting to me due to historical import.

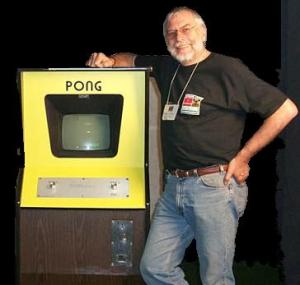

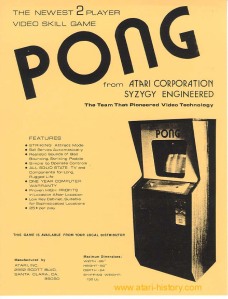

If you’re going to prop your legacy up on a fascinating behind-the-scenes story, you could do worse than Pong‘s. You have outsized personalities in a time and place ripe for change, and what’s more, they barely seemed to notice how deeply their own actions were affecting and propagating that evolution. Basically, Nolan Bushnell — the founder of Atari and shrieking-children-and-terrible-pizza-enthusiast hotspot Chuck E. Cheese’s — tried his best to get a Spacewar! knock-off called Computer Space into restaurants and bars around the country before realizing the game was too complex for somebody who just got off work and only wanted to pound some Budweisers. So, with the help of Allan Alcorn (working on a game he thought was just a simple design test), Pong was born in Computer Space‘s place. From there, many of the anecdotes about Pong‘s success deal in quarters. The original Pong machine was thought to be on the fritz because it became so overloaded with quarters; Atari employees had to carry thirty-pound bags of quarters with their wives in tow when unloading Pong machines in seedy California areas. I love that the origin story of the first video game production juggernaut begins in the currency of a five year-old’s allowance.

Bushnell’s persona and rich, infamous legacy are the most eye-catching factors in the Pong myth. There aren’t many other members of the video game industry who Leonardo DiCaprio would pursue playing in a biopic, but even though the Nolan Bushnell story never made it to the big screen, he’s still perhaps the most written-about figure in the history of games. He’s the proto-Silicon Valley mogul, setting us up for the likes of Steve Jobs. (Jobs famously met Steve Wozniak on an Atari project, as it so happens.) He embodies a lot of the reasons these ruthless, self-centered geniuses are viewed as benevolent demigods in our Information Age; who wouldn’t want a legitimate claim to making the world a better, more advanced place, especially one that also gave him license to be a crazy, rich asshole?

Perhaps that’s why Pong could never resonate like other founding video games. Its legacy and success is that of the businessman behind it, not its actual designer. And Allan Alcorn’s original game actually weaved its share of nuances into the simple premise. The paddles launch the ball at different angles depending upon the segment it hits, and the edges of the field originally could not be defended, imbibing the game with just enough opportunity for skill and chance that “rudimentary” did not quickly morph into “boring.” But while Bushnell was smart and talented enough to understand the reasons why the game worked so well, I’m not sure he truly cared about those aspects as long as it sold. As the true force of nature behind Pong and Atari, Bushnell’s drive for monetary success above all else limits our view of his company’s work when compared to, say, the optimism and creative liveliness of the nerds who poured their hearts and souls into Spacewar! Pong was key to the future of video games, but it was also indifferent to it. Perhaps it inadvertently led to the beauty, wit, and idiosyncrasies of other titles I have discussed, but it paved the way for the industry more than the art it would foster.

If there’s one element of Pong that’s still deeply ingrained in game design, it’s how technical wizardry can cover up repetitive, frankly uninteresting tasks. No one played Pong because they had a sudden fascination with table tennis; they flocked to it because it was the closest thing at the time to an actual virtual sport straight out of a science fiction novel. Developers can still convince players to spend hours on menial tasks because doing it in a video game makes it cool. It’s why we can play horseshoes in Red Dead Redemption, or chop wood in Fable II. It’s why you have an ungodly amount of hours racked up in countless grind-heavy RPGs and multiplayer shooters. I’m not ragging on it; when it works, it’s invisible. But I don’t think it’s noted enough how repetition is inherent to the limitations of the medium. Approximating different real world movements and tasks with a fairly limited design interface is difficult, and I applaud developers who don’t bite off more than they can chew. But really, in many ways, we’re still just bouncing that ball back and forth. Sometimes we bounce it back and forth by shooting a gun; sometimes by picking a dialogue option or selecting an appropriate magic spell. Video games are really a series of such small moments and decisions, implemented through a control scheme that has changed relatively little and repeated into infinity.

I actually haven’t played Pong since I was a kid (and even then, it was a Flash game recreation), but I imagine it holds up. Breathing is as popular as ever, after all, and the wheel still hasn’t gone out of fashion. Yet I still find it odd when people refer to it as a “classic” game. There are plenty of early films and novels regarded as “classics,” but they almost all have some emotional or thematic resonance beyond the date of their creation. It’s part of what makes video games so intriguing and yet so frustrating, that we can hold up a commerce-first piece of prehistoric design as one of the early beacons of the craft. But that shrewdness led to some great things, and maybe it’s okay that its achievements are more architectural than artistic. Someone has to build the house before you can decorate it.

===

Like on Facebook for future updates.

About 15 years ago my parents got satellite TV in France, there was the possibility of playing Pong with the remote control. I spent hours playing this- and I mean, that was already a really, really old fashioned game!!!

Pong wasn’t, isn’t a great game, but it’s a mesmerizing one. That’s not to say it couldn’t get boring, but there’s a fundamental addictiveness to it. Developers had to figure out ways to keep players playing — elevating Pong’s difficulty by gradual speeding up the ball is a nice example of that. It’s also another example of early “multiplayer.” As much as non-gamers love to exploit the stereotype of loner gamers in their parent’s basements, early games were meant to be enjoyed with and among others.

We had Pong on our Atari, and it was the only video game my entire family played, even my mother. We’d hand off the joysticks round robin-like, and it was silly but fun.

Another fantastic write-up by the way — really enjoyed reading this one.

That’s a great point. People really bemoan the shift toward multiplayer-focused games during the last decade, but video games really did start out as a social medium. It was literally impossible to play Pong alone on those early machines.

At the time Pong came out, it was revolutionary. My dad and a couple friends spent months putting together a tri-color version of Pong for their capstone project in college in 1979. While it’s a simple game, I wouldn’t discount its innovative properties.

Definitely not. I hope I didn’t come off as too dismissive because I do respect what the game did.